Exploring Westminster, London, England

Note: This post has been updated on September 30, 2023.

There are no shortage of things to do and see in London. Every time we come back, we find new areas to explore and new things to learn. Because of this, we have broken out our London post into several.

The below information is a complete guide of the best places to stay, the top rated places to dine and drink, and all there is to see and do in Westminster. For transportation tips, as well as a summary of the history of this amazing city, please refer back to the London post.

Jump To:

Where to Stay

While there are many areas to stay in, we have chosen the most popular to consider:

Where to Dine & Drink

Charlie’s

A high-end modern European option with a seasonally rotating menu served in an opulent hotel.

Ekstedt at The Yard

Scandinavian cuisine

Il Borro Tuscan Bistro

Serving Tuscan fare

Kerridge's Bar & Grill

Elegant, handsome eatery offering refined British comfort food from a Michelin-starred chef.

Kona

Known for their “secret garden” afternoon tea service (they have a fantastic gluten-free menu)

The Goring Dining Room

A Michelin-starred restaurant locally-inspired dishes

Yaatra

Modern Indian cuisine

Things to See & Do

Churchill Statue

The statue of Winston Churchill, in Parliament Square, is a bronze sculpture of the former British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

It’s located on a spot referred to in the 1950s by Churchill as "where my statue will go". It was unveiled in 1973 by his widow, Clementine, Baroness Spencer-Churchill, at a ceremony attended by the serving Prime Minister and four former Prime Ministers, while Queen Elizabeth II gave a speech.

The statue is one of twelve statues on or around Parliament Square, most of well-known statesmen.

#10 Downing street

10 Downing Street was originally three separate buildings: A mansion (know as “The House at the Back”, a townhouse, and a cottage. Downing, a notorious spy for Oliver Cromwell and later Charles II, invested in property and acquired considerable wealth. In 1654, he purchased the lease on land south of St James's Park, adjacent to the House at the Back, within walking distance of parliament. Downing planned to build a row of terraced town houses "for persons of good quality to inhabit in .” However, The Hampden family had a lease on the land that they refused to relinquish. Downing fought their claim, but failed and had to wait 30 years before he could build. When the Hampden lease expired, Downing received permission to build on land further west to take advantage of more recent property developments. Between 1682 and 1684, Downing built a cul-de-sac of two-storey town houses with coach-houses, stables, and views of St James's Park. Over the years, the addresses changed several times. In 1787 Number 5 became "Number 10".

The "House at the Back", the largest of the three houses, which were combined to make Number 10, was a mansion built in about 1530 next to Whitehall Palace. Rebuilt, expanded, and renovated many times since, it was originally one of several buildings that made up the "Cockpit Lodgings", so-called because they were attached to an octagonal structure used for cock-fighting. Early in the 17th century, the Cockpit was converted to a concert hall and theatre; after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, some of the first cabinet meetings were held there secret.

From that time, the "House at the Back" was usually occupied by members of the royal family or the government. Princess Elizabeth, eldest daughter of King James I, lived there from 1604 until 1613 when she married Frederick V, Elector Palatine and moved to Heidelberg. She was the grandmother of King George I, the Elector of Hanover, who became King of Great Britain in 1714, and was the great-grandmother of King George II, who presented the house to Robert Walpole in 1732. Walpole accepted on the condition that the gift was to the office of First Lord of the Treasury. The post of First Lord of the Treasury has, for much of the 18th and 19th centuries, and invariably since 1905, been held by the prime minister. Walpole commissioned William Kent to join the three houses, which effectively made the building 100 rooms in total.

Walpole lived in Number 10 until 1742. Although he had accepted it on behalf of future First Lords of the Treasury, it would be 21 years before any of his successors chose to live there - the five who followed Walpole preferred their own homes. This was the pattern until the beginning of the 20th century. Of the 31 First Lords from 1735 to 1902, only 16 (including Walpole) lived in Number 10, arguably because their own townhomes were more luxurious and larger in size. It was also due to the fact that the building was prone to sinking because it was built on soft soil and a shallow foundation - floors buckled and walls and chimneys cracked. It became unsafe and frequently required repairs.

Downing Street declined at the turn of the 19th century, becoming surrounded with run-down buildings, dark alleys, and the scene of crime and prostitution. Earlier, the government had taken over the other Downing Street houses: the Colonial Office occupied Number 14 in 1798; the Foreign Office was at Number 16 and the houses on either side; the West India Department was in Number 18; and the Tithe Commissioners in Number 20. The houses deteriorated from neglect, became unsafe, and one by one, were demolished. By 1857, Downing Street's townhouses were all gone except for Number 10, Number 11 (customarily the Chancellor of the Exchequer's residence), and Number 12 (used as offices for Government Whips). In 1879, a fire destroyed the upper floors of Number 12 and was renovated as a single-story structure.

By the middle of the 20th century, Number 10 was falling apart again. The deterioration had been obvious for some time. The number of people allowed in the upper floors was limited for fear the bearing walls would collapse. The staircase had sunk several inches, with some steps buckled and the balustrade was out of alignment. Dry rot was widespread throughout. The interior wood in the Cabinet Room's double columns was like sawdust. Skirting boards, doors, sills, and other woodwork were riddled and weakened with disease. After reconstruction had begun, miners dug down into the foundations and found that the huge wooden beams supporting the house had decayed. It was then decided that the building’s importance was on-par with the palaces and proper architects and teams were hired. It took £3,000,000 and three years to complete the repairs and restoration.

The new foundation was made of steel-reinforced concrete with pilings sunk 6 to 18 feet. The "new" Number 10 consisted of about 60% new materials; the remaining 40% was either restored or replicas of originals. Many rooms and sections of the new building were reconstructed exactly as they were in the old Number 10. These included: the garden floor, the door and entrance foyer, the stairway, the hallway to the Cabinet Room, the Cabinet Room, the garden and terrace, the Small and Large State Rooms, and the three reception rooms. The staircase, however, was rebuilt and simplified. Steel was hidden inside the columns in the Pillared Drawing Room to support the floor above. The upper floors were modernised and the third floor extended over Numbers 11 and 12 to allow more living space. As many as 40 coats of paint were stripped from the elaborate cornices in the main rooms revealing details unseen for almost 200 years in some cases.

When builders examined the exterior façade, they discovered that the black colour visible, even in photographs from the mid-19th century, was misleading - the bricks were actually yellow. The black appearance was the product of two centuries of pollution. To preserve the 'traditional' look of recent times, the newly cleaned yellow bricks were painted black to resemble their well-known appearance.

Since then, several more restoration and modernization projects have been completed, especially when it came to Prime Ministers with large families who needed more room to accommodate.

Big Ben

Elizabeth Tower (originally called the, “Clock Tower”), but more popularly known as “Big Ben”, was raised as a part of Charles Barry's design for a new Palace of Westminster, after the old palace was largely destroyed by fire on October 16, 1834. Construction of the tower began on September 28, 1843 and completed in 1859. It stands 316 feet high, making it the third tallest clock tower in the UK. Its dials (at the center) are 180 feet above ground level. The tower's base is square, measuring 40 feet on each side, resting on concrete foundations 12 feet thick. It was constructed using bricks clad on the exterior with sand-coloured Anston limestone from South Yorkshire, topped by a spire covered in hundreds of cast-iron roof tiles. There is a spiral staircase with 290 stone steps up to the clock room, followed by 44 to reach the belfry, and an additional 59 to the top of the spire.

Above the belfry and Ayrton light are 52 shields decorated with national emblems of the four countries of the UK: the red and white rose of England's Tudor dynasty, the thistle of Scotland, shamrock of Northern Ireland, and leek of Wales. They also feature the pomegranate of Catherine of Aragon, first wife of the Tudor king Henry VIII; the portcullis, symbolising both Houses of Parliament; and fleurs-de-lis - a legacy from when English monarchs claimed to rule France.

A ventilation shaft running from ground level, up to the belfry, which measures 16 x 8 feet, was designed to draw cool, fresh air into the Palace of Westminster (in practice, this did not work and the shaft was repurposed as a chimney, until around 1914). The 2017–2021 conservation works included the addition of a lift that was installed in the shaft.

Its foundations rest on a layer of gravel, below which is London clay. Owing to this soft ground, the tower leans slightly to the north-west by roughly 9.1 in. In the 1990s, thousands of tons of concrete were pumped into the ground, underneath the tower, to stabilize it during construction of the Westminster section of the Jubilee line. It leans by 20 in. at the finial. Experts believe the tower's lean will not be a problem for another 4,000 to 10,000 years.

“Fun fact”: Inside the tower is an oak-panelled Prison Room, which can only be accessed from the House of Commons, not via the tower entrance. It was last used in 1880 when atheist Charles Bradlaugh, newly elected Member of Parliament for Northampton, was imprisoned by the Serjeant at Arms after he protested against swearing a religious oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria. Officially, the Serjeant at Arms can still make arrests, as they have had the authority to do, since 1415. The room, however, is currently occupied by the Petitions Committee, which oversees petitions submitted to Parliament.

Buckingham Palace

The first house erected within the Buckingham Palace site was that of Sir William Blake, around 1624. The next owner was Lord Goring, who from 1633, extended Blake's house, which came to be known as “Goring House”, and developed much of today's garden, then known as “Goring Great Garden”. When the improvident Goring defaulted on his rents, Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, was able to purchase the lease of Goring House and he was occupying it when it burned down in 1674, following which he constructed Arlington House on the site – the location of the southern wing of today's palace – the next year. In 1698, John Sheffield acquired the lease. He later became the first Duke of Buckingham and Normandy, and “Buckingham House” was built for him in 1703 to the design of William Winde. The style chosen was of a large, three-floored central block with two smaller flanking service wings. It was eventually sold by Buckingham's illegitimate son, Sir Charles Sheffield, in 1761 to George III for £21,000. Sheffield's leasehold on the garden site, the freehold of which was still owned by the royal family, was due to expire in 1774.

Under the new royal ownership, the building was originally intended as a private retreat for Queen Charlotte, and was accordingly known as “The Queen's House”. Remodelling of the structure began in 1762. In 1775, an Act of Parliament settled the property on Queen Charlotte, in exchange for her rights to nearby Somerset House, and 14 of her 15 children were born there. Some furnishings were transferred from Carlton House and others had been bought in France after the French Revolution of 1789. While St James's Palace remained the official and ceremonial royal residence, the name "Buckingham-palace" was used from at least 1791.

After his accession to the throne in 1820, George IV continued the renovation intending to create a small, comfortable home. However, in 1826, while the work was in progress, the King decided to modify the house into a palace. On the death of George IV in 1830, his younger brother, William IV, hired Edward Blore to finish the work, though William never moved into the palace. After the Palace of Westminster was destroyed by fire in 1834, he offered to convert Buckingham Palace into a new Houses of Parliament, but his offer was declined.

Buckingham Palace became the principal royal residence in 1837, on the accession of Queen Victoria, who was the first monarch to reside there. While the state rooms were a riot of gilt and colour, the necessities of the new palace were somewhat less luxurious. It was reported the chimneys smoked so much that the fires had to be allowed to die down, and consequently, the palace was often cold. Ventilation was so bad that the interior smelled, and when it was decided to install gas lamps, there was a serious worry about the buildup of gas on the lower floors. It was also said that the staff were lax and lazy and the palace was dirty. Following the Queen's marriage in 1840, her husband, Prince Albert, concerned himself with a reorganization of the household offices and staff, and with addressing the design faults of the palace. By the end of 1840, all the problems had been rectified. However, the builders were to return within a decade.

By 1847, the couple had found the palace too small for court life and their growing family, and a new wing was built. The large East Front, facing The Mall, is today the "public face" of Buckingham Palace and contains the balcony from which the royal family acknowledge the crowds on momentous occasions and after the annual Trooping the Colour. The ballroom wing and a further suite of state rooms were also built in this period. Before Prince Albert's death, the palace was frequently the scene of musical entertainments, as well as lavish costume balls, in addition to the usual royal ceremonies, investitures and presentations.

Widowed in 1861, the grief-stricken Queen withdrew from public life and left Buckingham Palace to live at Windsor Castle, Balmoral Castle, and Osborne House. For many years, the palace was seldom used, even neglected. Eventually, public opinion persuaded the Queen to return to London, even though she preferred to live elsewhere whenever possible. Court functions were still held at Windsor Castle, presided over by the sombre Queen, habitually dressed in mourning black, while Buckingham Palace remained shuttered for most of the year.

In 1901, the new king, Edward VII, began redecorating the palace. The King and his wife, Queen Alexandra, had always been at the forefront of London high society, and their friends, known as "the Marlborough House Set", were considered to be the most eminent and fashionable of the age. Buckingham Palace—the Ballroom, Grand Entrance, Marble Hall, Grand Staircase, vestibules and galleries were redecorated in the Belle Époque cream and gold colour scheme they retain today—once again, became a setting for entertaining on a majestic scale.

During WWI, which lasted from 1914 until 1918, the palace escaped unscathed. Its more valuable contents were evacuated to Windsor, but the royal family remained in residence. The King imposed rationing at the palace, much to the dismay of his guests and household.

George V's wife, Queen Mary, was a connoisseur of the arts and took a keen interest in the Royal Collection of furniture and art, both restoring and adding to it. Queen Mary also had many new fixtures and fittings installed, such as the pair of marble Empire-style chimneypieces by Benjamin Vulliamy, dating from 1810, which the Queen had installed in the ground floor Bow Room. Queen Mary was also responsible for the decoration of the Blue Drawing Room (a 69-foot room, once known as the “South Drawing Room”. In 1938, the northwest pavilion, designed as a conservatory, was converted into a swimming pool.

During WWII, which broke out in 1939, the palace was bombed nine times, with the most serious and publicized incident being the destruction of the palace chapel in 1940. One bomb fell in the palace quadrangle while George VI and Queen Elizabeth (the future Queen Mother) were in the palace, and many windows were blown in.

In 1962, a purpose-built gallery opened. In 1968, Charles Tryon, 2nd Baron Tryon, acting as treasurer to Queen Elizabeth II, sought to exempt Buckingham Palace from full application of the Race Relations Act 1968. He stated that the palace did not hire people of colour for clerical jobs, only as domestic servants. He arranged with Civil servants for an exemption that meant that complaints of racism against the royal household would be sent directly to the Home Secretary and kept out of the legal system.

The Government of the United Kingdom is responsible for maintaining the palace in exchange for the profits made by the Crown Estate. In 2015, the State Dining Room was closed for a year and a half because its ceiling had become potentially dangerous. A 10-year schedule of maintenance work, including new plumbing, wiring, boilers and radiators, and the installation of solar panels on the roof, has been estimated to cost £369 million and was approved by the prime minister in November 2016. It will be funded by a temporary increase in the Sovereign Grant paid from the income of the Crown Estate and is intended to extend the building's working life by at least 50 years.

OUR EXPERIENCE: We were able to see the main state rooms, a coronation exhibit, as well as the main meeting room that the King meets with the Prime Minister in. We were also able to visit the back gardens that led to the exit quite a ways down. It’s definitely worth the price of admission!

TIP ON VISITING: They only sell a limited amount of tickets each day for only a few months each year. If you do snag a ticket, you will enter through Gate C - if you’re facing the palace, go to the left and head to the end. Turn right down the sidewalk and at the end, turn right again. You will see a white sign with “Gate C” on your right about 1/3 of the way down.

Changing of the Guard

Household Troops have guarded the Sovereign and the Royal Palaces since 1660. When Queen Victoria moved into Buckingham Palace in 1837, the Queen's Guard remained at St James's Palace, with a detachment guarding Buckingham Palace, as it still does today. The Changing of the Guard ceremony marks the moment when the soldiers currently on duty, the Old Guard, exchange places with the New Guard.

The guard duties are normally provided by a battalion of the Household Division, but also sometimes by other infantry battalions or units. For example, around the time of the Queen's Coronation in 1953, soldiers from Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Ceylon and Pakistan all participated in the Changing of the Guard, and today we regularly see regiments from across the Commonwealth, as well as from the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy, performing Changing the Guard.

Churchill War Rooms

In 1936, the Air Ministry believed that in the event of war, enemy aerial bombing of London would cause up to 200,000 casualties per week. British government commissions, under Warren Fisher and Sir James Rae, in 1937 and 1938, considered that key government offices should be dispersed from central London to the suburbs, and nonessential offices to the Midlands or North West. Pending this dispersal, in March 1938, Sir Hastings Ismay, then Deputy Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence, ordered an Office of Works survey of Whitehall to identify a suitable site for a temporary emergency government centre for use during bombing raids. Although it is commonplace for present-day governments to operate such facilities, this was the first time the British government had required one, as such, there was no precedent for how or where it should be built, or what it should contain.

In May, as German troops were gathering on the border with Czechoslovakia, the Office concluded the most suitable site was the basement of the New Public Offices (NPO) - a government building located on the corner of Horse Guards Road and Great George Street, near Parliament Square. The building now accommodates HM Treasury. In 1938, work to convert the basement of the NPO began, which included installing communications and broadcasting equipment, soundproofing, ventilation, and reinforcement. Because the War Rooms are below the level of the River Thames, flood doors and pumps were installed to prevent flooding. Meanwhile, by the summer of 1938, the War Office, Admiralty and Air Ministry, had developed the concept of a Central War Room that would facilitate discussion and decision-making between the Chiefs of Staff of the armed forces.

As ultimate authority lay with the civilian government, the Cabinet, or a smaller War Cabinet, would require close access to senior military figures. This implied accommodation close to the armed forces' Central War Room. In May 1939, it was decided that the Cabinet would be housed within the Central War Room. In August 1939, with war imminent and protected government facilities in the suburbs not yet ready, the War Rooms became operational on August 27, 1939, only days before the invasion of Poland on September 1st, and Britain's declaration of war on Germany on September 3rd.

Staff accessed the War Rooms via, the main entrance of the NPO, and once inside the building, descended down Staircase 15, entering near to the Churchills' kitchen. Following Winston Churchill's appointment as Prime Minister, Churchill visited the Cabinet Room in May 1940 and declared: 'This is the room from which I will direct the war'. On October 22, 1940, during the Blitz bombing campaign against Britain, it was decided to increase the protection of the Cabinet War Rooms by the installation of a massive layer of concrete known as 'the Slab'. Up to 5 feet thick, the Slab was progressively extended and by spring 1941, the increased protection had enabled the Cabinet War Rooms to expand to three times their original size. While the usage of many of the individual rooms changed over the course of the war, the facility included dormitories for staff, private bedrooms for military officers and senior ministers, and rooms for typists or telephone switchboard operators. Two other notable rooms include the Transatlantic Telephone Room and Churchill's office-bedroom. From 1943, a SIGSALY code-scrambling encrypted telephone was installed in the basement of Selfridges, Oxford Street, connected to a similar terminal in the Pentagon building. This enabled Churchill to speak securely with President Roosevelt in Washington, with the first conference taking place on July 15, 1943. Later extensions were installed to both 10 Downing Street and the specially constructed Transatlantic Telephone Room within the Cabinet War Rooms.

Churchill's office-bedroom included BBC broadcasting equipment, of which Churchill made four wartime broadcasts. Churchill rarely slept underground, preferring to sleep at 10 Downing Street or the No.10 Annexe, a flat in the NPO directly above the Cabinet War Rooms. His daughter Mary Soames often slept in the bedroom allocated to Mrs Churchill.

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered, bringing an end to the war. The following day, the lights in the Map Room were simply turned off and the staff vacated their offices. Several were cleared and used for other purposes, but the Cabinet Room, Map Room, Transatlantic Telephone Room and Churchill's bedroom were preserved for their historic value.

In 2005, the War Rooms were rebranded as the “Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms”, with 9,100 sq. ft. of the site redeveloped as a biographical museum exploring Churchill's life.

Fortnum and Mason

William Fortnum was a footman in the household of Queen Anne. The royal family's insistence on having new candles every night resulted in large amounts of half-used wax, which Fortnum promptly resold. Fortnum also had a side business as a grocer. He convinced his landlord, Hugh Mason, to be his associate, and they founded the first Fortnum & Mason store, in Mason's small shop, in St James's Market, in 1707. In 1761, William Fortnum's grandson, Charles, went into the service of Queen Charlotte, and the connection with the royal court led to an increase in business. The store began to stock speciality items, namely ready-to-eat luxury meals, such as poultry or game served in aspic jelly.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the emporium supplied dried fruit, spices and other preserves to British officers and during the Victorian era, it was frequently called upon to provide food for prestigious court functions. Queen Victoria sent shipments of Fortnum & Mason's concentrated beef tea to Florence Nightingale's hospitals during the Crimean War.

In 1886, after having bought the entire stock of five cases of a new product made by H. J. Heinz, Fortnum & Mason became the first store in Britain to stock tins of baked beans.

In April 1951, the Canadian businessman, W. Garfield Weston, acquired the store and became its chairman following a boardroom coup. In 1964, he commissioned a four-ton clock to be installed above the main entrance of the store as a tribute to its founders (see below for the history on it).

Fun fact: Fortnum & Mason claims to have invented the Scotch egg, in 1738.

The Fortnum and Mason Clock

The upscale department store of Fortnum & Mason, on Piccadilly, also has something else wonderful to offer. Outside, high on the wall, over the entrance, is an ornamental clock standing 10 feet tall and weighing in excess of four tons.

The clock was commissioned in 1964 by the shop’s owner, W. Garfield Weston. It has 18 bells, which were cast at the renowned Whitechapel Bell Foundry—the same place that cast the bells for Big Ben. The bells chime every 15 minutes and play 18th-century airs. At the top of every hour, a pair of four-foot-tall figures, depicting William Fortnum and Hugh Mason, the men who founded the shop, come out to bow to each other.

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank of the River Thames in the City of Westminster, in central London.

Its name, which derives from the neighboring Westminster Abbey, is owned by the Crown. Committees appointed by both houses manage the building and report to the Speaker of the House of Commons and to the Lord Speaker.

The first royal palace constructed on the site dated from the 11th century, and after the Tower of London, Westminster became the primary residence of the Kings of England until fire destroyed the royal apartments in 1512. The remainder of the palace continued to serve as the home of the Parliament of England, which had met there since the 13th century, and also as the seat of the Royal Courts of Justice, based in and around Westminster Hall. In 1834, an even greater fire ravaged the heavily rebuilt Houses of Parliament, and the only significant medieval structures to survive were Westminster Hall, the Cloisters of St Stephen's, the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft, and the Jewel Tower.

The remains of the Old Palace (except the detached Jewel Tower) were incorporated into its much larger replacement, which contains over 1,100 rooms organized symmetrically around two series of courtyards and which has a floor area of 1,210,680 sq. ft.. Part of the New Palace's area of 8 acres was reclaimed from the River Thames, which is the setting of its nearly 980 ft. façade, called the “River Front”. Construction started in 1840 and lasted for 30 years, suffering great delays and cost overruns, as well as the death of both leading architects. Works for the interior decoration continued, intermittently, well into the 20th century. Major conservation work has taken place since then to reverse the effects of London's air pollution, and extensive repairs followed WWII, including the simplified reconstruction of the Commons Chamber following its bombing in 1941.

The Palace of Westminster has been a Grade I listed building, since 1970, and part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, since 1987.

Piccadilly Circus

Piccadilly has been a main thoroughfare, since at least medieval times, and in the Middle Ages, was known as "the road to Reading" or "the way from Colnbrook". Around 1611 or 1612, Robert Baker acquired land in the area, and prospered by making and selling piccadills. Shortly after purchasing the land, he enclosed it and erected several dwellings, including his home, Pikadilly Hall. (At the time, the street was named Portugal Street in 1663, after Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II, and grew in importance after the road from Charing Cross to Hyde Park Corner was closed to allow the creation of Green Park, in 1668).

Some of the most notable stately homes in London were built on the northern side of the street during this period, including Clarendon House and Burlington House in 1664. Berkeley House, constructed around the same time as Clarendon House, was destroyed by a fire in 1733 and rebuilt as Devonshire House in 1737 by William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire. It was later used as the main headquarters for the Whig party. Burlington House has since been home to several noted societies, including the Royal Academy of Arts, the Geological Society of London, the Linnean Society, and the Royal Astronomical Society. Several members of the Rothschild family had mansions at the western end of the street. St James's Church was consecrated in 1684 and the surrounding area became St James Parish.

The Old White Horse Cellar, at No. 155, was one of the most famous coaching inns in England by the late 18th century, by which time the street had become a favored location for booksellers. The Bath Hotel emerged around 1790, and Walsingham House was built in 1887. Both the Bath and the Walsingham were purchased and demolished, and the prestigious Ritz Hotel built on their site in 1906. Piccadilly Circus station, at the east end of the street, was opened in 1906 and rebuilt between 1925 and 1928. The clothing store, Simpson's, was established at Nos. 203–206 Piccadilly in 1936.

During the 20th century, Piccadilly became known as a place to acquire heroin, and was notorious in the 1960s as the center of London's illegal drug trade. Today, it is regarded as one of London's principal shopping streets. Its landmarks include the Ritz, Park Lane, Athenaeum and Intercontinental hotels, Fortnum & Mason, the Royal Academy, the RAF Club, Hatchards, the Embassy of Japan, and the High Commission of Malta.

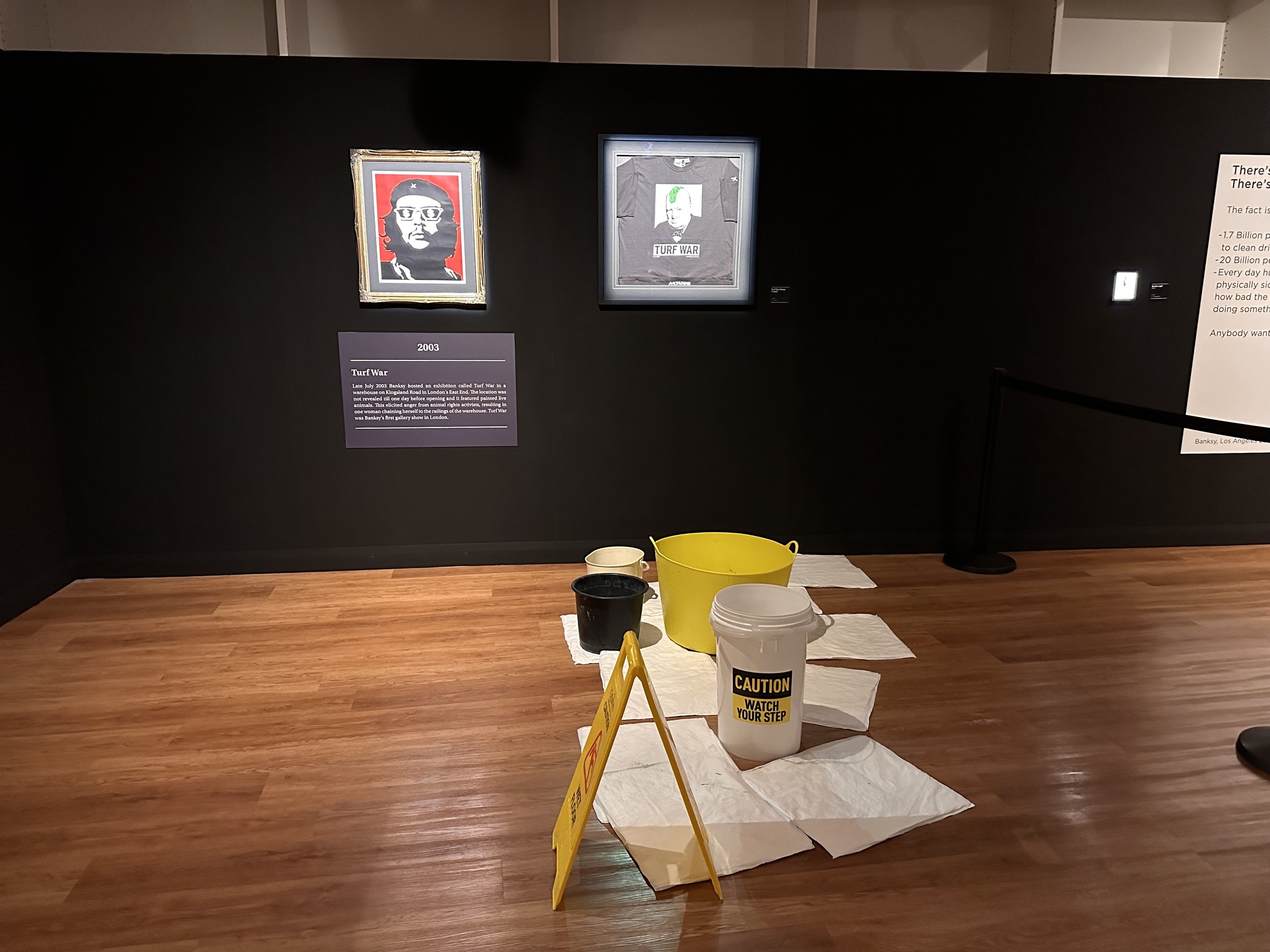

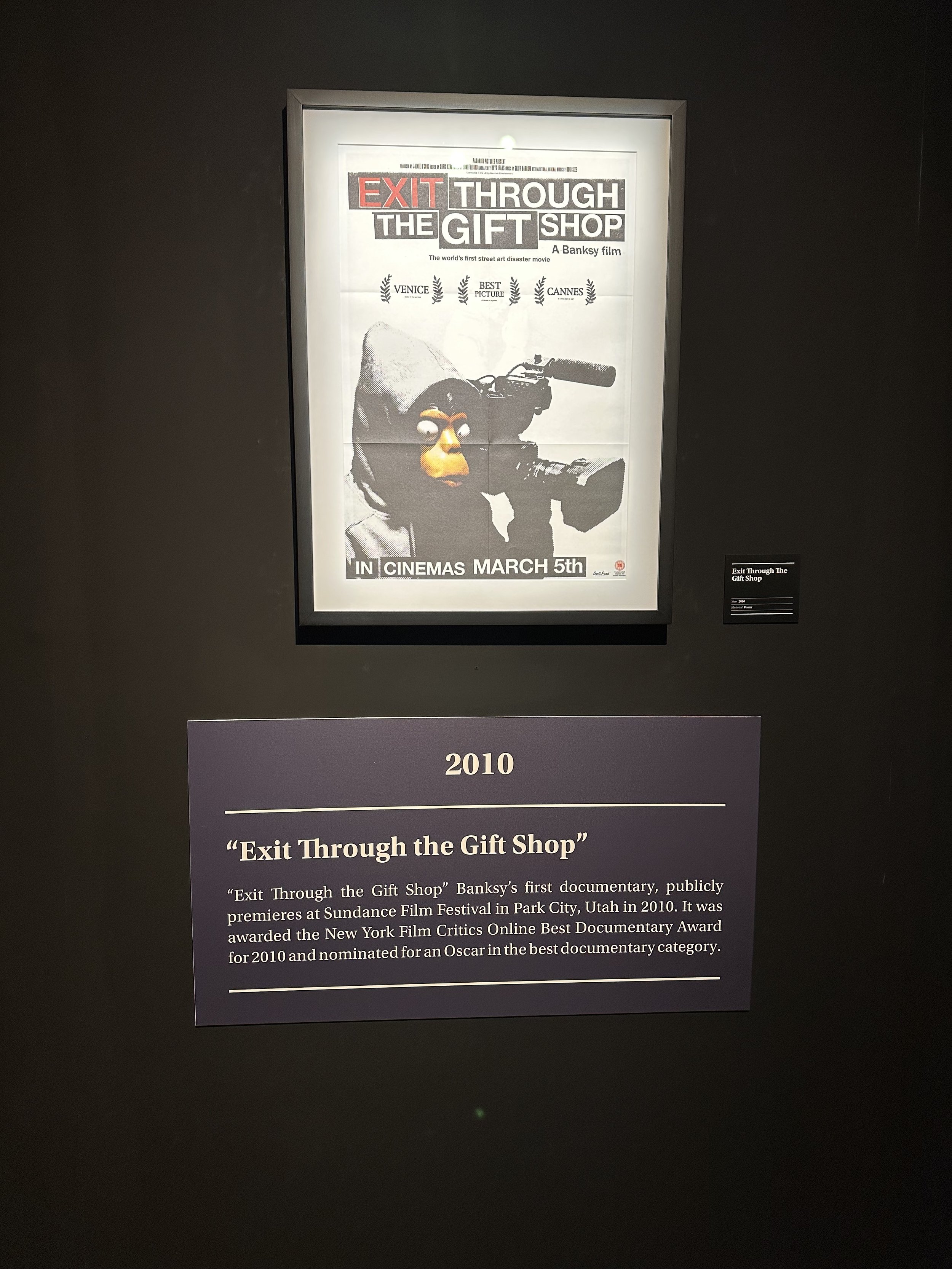

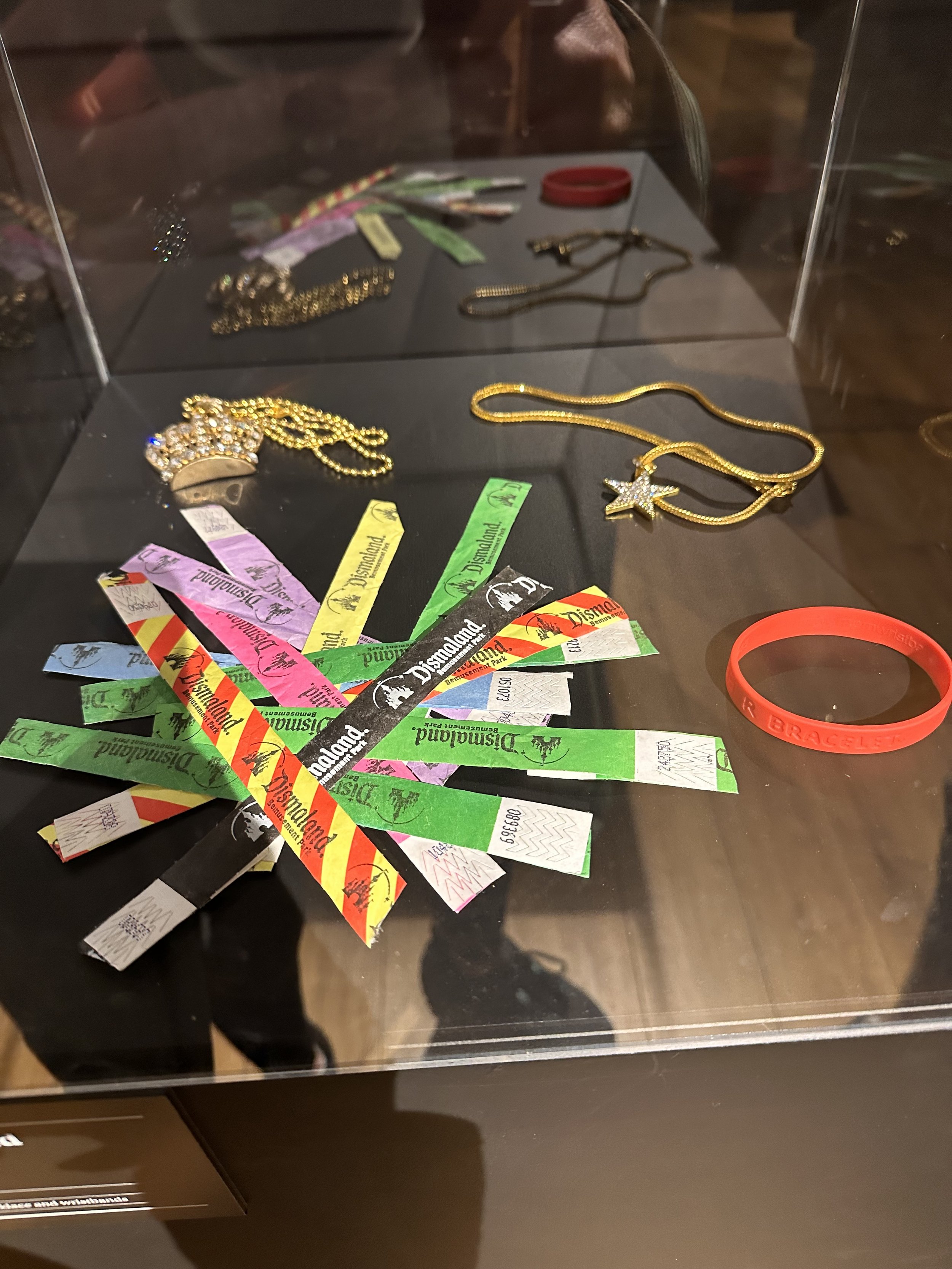

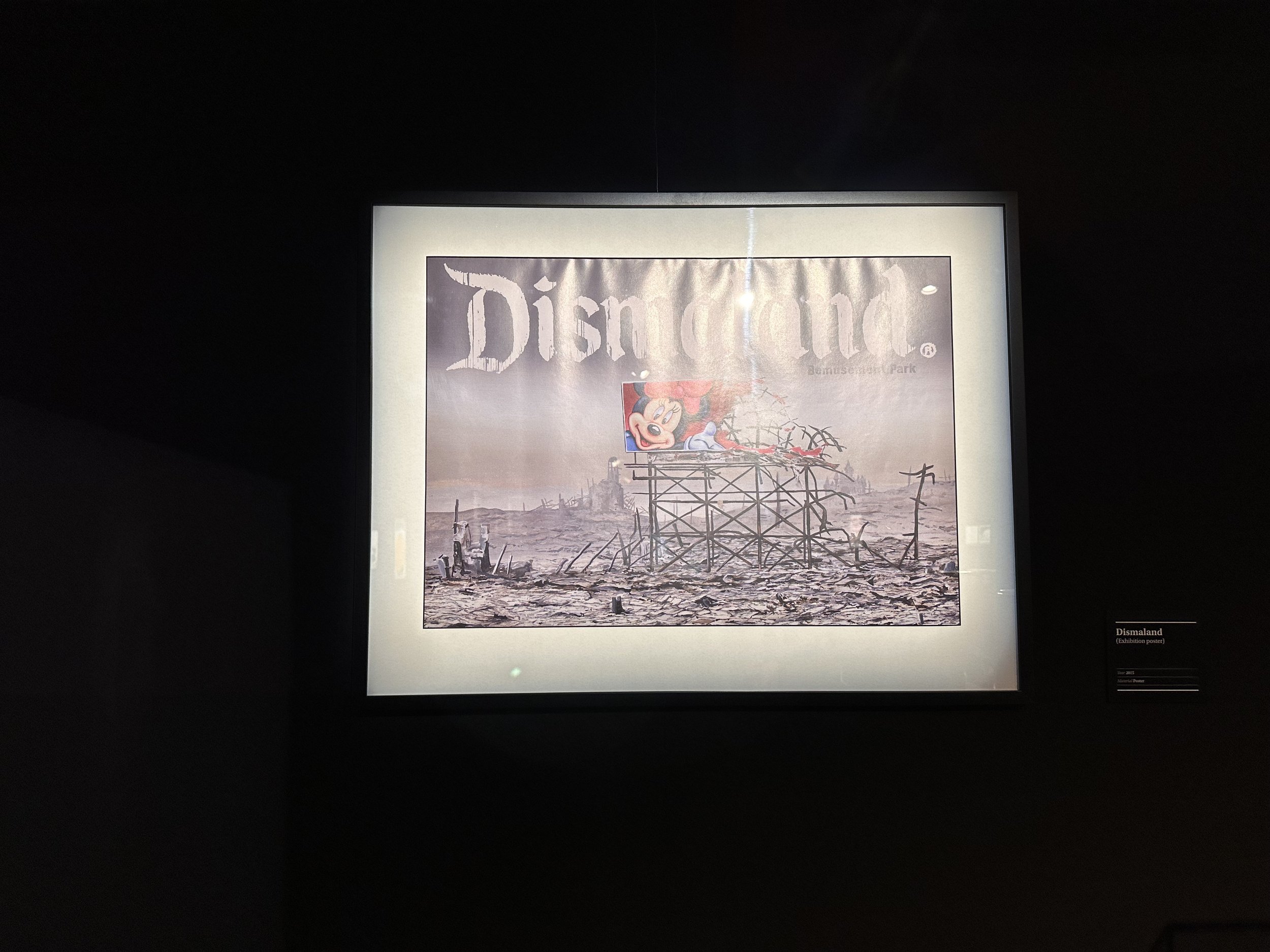

The Art of Banksy

The Art of Banksy is the world’s largest collection of original and authenticated Banksy artworks showcasing more than 150 pieces including prints, canvases, unique works and ephemera, many of which are on public display for the very first time.

OUR EXPERIENCE: We stumbled upon it and were so glad we decided to go in. It was amazing to see other pieces of his work (including Dismaland) and see interviews from some of his co-artists!

The National Gallery

Founded in 1824, and in Trafalgar Square since 1838, the National Gallery houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century, to 1900. Its collection belongs to the government, on behalf of the British public, and entry to the main collection is free of charge.

Unlike comparable museums in continental Europe, the National Gallery was not formed by nationalizing an existing royal or princely art collection. It came into being when the British government bought 38 paintings from the heirs of John Julius Angerstein in 1824. After that initial purchase, the Gallery was shaped mainly by its early directors, especially Charles Lock Eastlake, and by private donations, which now account for two-thirds of the collection. The collection is smaller than many European national galleries. It used to be claimed that this was one of the few national galleries that had all its works on permanent exhibition, but this is no longer the case.

The present building, the third site to house the National Gallery, took from 1832 to 1838 to be built. Only the facade onto Trafalgar Square remains essentially unchanged from this time, as the building has been expanded, piecemeal, throughout its history.

The National Portrait Gallery

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London that houses a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. When it opened in 1856, it was arguably the first national public gallery in the world that was dedicated to portraits.

The gallery moved in 1896 to its current site, at St Martin's Place, off Trafalgar Square, and adjoining the National Gallery. The National Portrait Gallery also has regional outposts at Beningbrough Hall in Yorkshire and Montacute House in Somerset.

In January 2008, the Gallery received its largest single donation to date, a £5m gift from US billionaire, Randy Lerner.

In January 2012, Catherine, (then Duchess of Cambridge), announced the National Portrait Gallery as one of her official patronages. Her portrait was unveiled in January 2013.

In June 2017, it was announced that the NPG has been awarded funding of £9.4 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund towards its major transformation program, “Inspiring People” - the Gallery's biggest ever development. It just recently opened on June 23, 2023.

Tip: Click here to learn about the Monty Python foot and how to view it.

The Vincent Street Fireplace

During the Blitz bombings of WWII, much of London was reduced to rubble. With over 40,000 civilian deaths and over a million homes destroyed, the German bombing campaign left much of the city in ruins. On Vincent Street, alone, one attack saw 21 properties so badly hit that they were deemed “damaged beyond repair.” From the October 7, 1940 to June 6, 1941, 64 incendiary explosives were dropped on the area of Vincent Square Ward.

A lone reminder still stands of that bombing aftermath, and though the surrounding terrace house it belonged to was decimated, this small red brick fireplace survived the bombing campaign. The fireplace has stood as a reminder for more than 80 years since.

How to find: The fireplace can be found opposite Napier Hall (15B Vincent Square), on the left-hand side of the black wrought iron gates, to the car park of the brick flats opposite.

If you stand with your back to the memorial stone on the side of Napier Hall, it is directly in front of you, on the far side of a small hedge, close to the intersection of Vincent Street and Hide Place.

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square was established in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. The Square's name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar - the British naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars over France and Spain that took place on October 21, 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar.

The site around Trafalgar Square had been a significant landmark since the 1200s. For centuries, distances measured from Charing Cross have served as location markers. The site of the present square formerly contained the elaborately designed, enclosed courtyard, King's Mews. After George IV moved the mews to Buckingham Palace, the area was redeveloped by John Nash, but progress was slow after his death, and the square did not open until 1844. The 169-foot Nelson's Column at its center is guarded by four lion statues. A number of commemorative statues and sculptures occupy the square, but the Fourth Plinth, left empty since 1840, has been host to contemporary art, since 1999. Prominent buildings facing the square include the National Gallery, St Martin-in-the-Fields, Canada House, and South Africa House.

The square has been used for community gatherings and political demonstrations, including Bloody Sunday in 1887, the culmination of the first Aldermaston March, anti-war protests, and campaigns against climate change. A Christmas tree has been donated to the square by Norway, since 1947, and is erected for twelve days before and after Christmas Day. The square is a center of annual celebrations on New Year's Eve.

Victoria Palace Theatre

The theatre began life as a small concert room above the stables of the Royal Standard Hotel - a small hotel and tavern, built in 1832, at what was then 522 Stockbridge Terrace, on the site of the present theatre. The proprietor, John Moy, enlarged the building, and by 1850, it became known as Moy's Music Hall. Alfred Brown took it over in 1863, refurbished it, and renamed it the Royal Standard Music Hall.

The hotel was demolished in 1886, by which time the main line terminus, Victoria Station, and its new Grosvenor Hotel, had transformed the area into a major transport hub. The railways were, at this time, building grand hotel structures at their termini, and Victoria was one of the first. Added to this was the integration of the electric underground system and the building of Victoria Street.

The Royal Standard was demolished in 1910, and in its place, was built the current theatre, The Victoria Palace. It was designed by prolific theatre architect, Frank Matcham, and opened November 6, 1911. The original design featured a sliding roof that helped cool the auditorium during intervals in the summer months.

Under impresario Alfred Butt, the Victoria Palace Theatre continued the musical theatre tradition by presenting mainly varieties, and under later managements, repertory and revues. Perhaps because of its music hall linkage, the plays were not always taken seriously. In 1934, the theatre presented Young England - a patriotic play written by the Rev. Walter Reynolds, then 83. It received such amusingly bad reviews that it became a cult hit and played to full houses for 278 performances before transferring to two other West End theatres.

A return to revue brought new success. Me and My Girl was a hit in its original production at the theatre, opening in 1937, starring Lupino Lane. In 1939, songs from this show formed the first live broadcast of a performance by the BBC, and listeners could sing along to “The Lambeth Walk”. In early 1945, towards the end of the war in Europe, variety was presented under the stewardship of Lupino Lane. Headlining the bill from his radio series was Will Hay, with his schoolboy retinue of Charles Hawtrey and John Clark, and among the "turns" was Stainless Stephen, a comic acrobat/comedian duo, and Victor Barna (then world champion table tennis player) giving an exhibition, who would invite audience members up on to the stage to see if they could beat him in ten points. From 1947 through 1962, Jack Hylton produced The Crazy Gang series of comedy revues, with a glittering company of variety performers including Flanagan and Allen, Nervo and Knox, and Naughton and Gold.

The long-running Black and White Minstrel Show played through the 1960s until 1972. In 1982, a production of The Little Foxes, saw Elizabeth Taylor making her London stage debut. Another unusually long-running show at the theatre was Buddy – The Buddy Holly Story, that played for 13 years in London, beginning in 1989 (transferring to the Strand Theatre in 1995). After this, the theatre presented mostly revivals of well-known musicals. In 2005, Billy Elliot the Musical opened, garnering rave reviews and Olivier Awards.

The theatre was purchased by Stephen Waley-Cohen in 1991. In 2014, the theatre was sold to Delfont Mackintosh Theatres. After Billy Elliot ended its run in April 2016, the theatre closed for a multi-million pound refurbishment. In December 2017, the Broadway musical Hamilton re-opened the refurbished Victoria Palace.

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled, the “Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster”, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British monarchs, and a burial site for 18 English, Scottish, and British monarchs. At least 16 royal weddings have occurred at the abbey since 1100.

Although the origins of the church are obscure, there was certainly an abbey operating on the site by the mid-10th century, housing Benedictine monks. The church got its first grand building in the 1060s, under the auspices of the English king Edward the Confessor, who is buried inside. Construction of the present church began in 1245 on the orders of Henry III. The monastery was dissolved in 1559 and the church was made a royal peculiar—a Church of England church responsible directly to the sovereign—by Elizabeth I. In 1987, the abbey, together with the Palace of Westminster and St. Margaret's Church, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site because of its outstanding universal value.

The abbey is the burial site of more than 3,300 people, many of prominence in British history: monarchs, prime ministers, poets laureate, actors, scientists, military leaders, and the Unknown Warrior. Describing the fame of the figures buried there, author William Morris described the abbey in 1900 as a "National Valhalla".

TIP: In the attic of the Abbey, you will now find the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries.